OVERTURNED DEFENSE VERDICT, ADDS TO JURY AWARDS

Judge Toal has a record of overturning or modifying jury verdicts with which she disagrees.

For example, in a 2018 case, after Covil Corp. said it could not produce old documents because the papers had been destroyed in a fire, the court found that spoliation occurred and sanctioned the company with an adverse instruction effectively telling the jurors to presume the company exposed the plaintiff to asbestos in his workplace.

The judge did this even though the plaintiff did not identify Covil in his deposition and a representative for another company, Daniel Construction, testified that did not have any records indicating that Covil supplied insulation for the plaintiff’s workplace and could not definitively place Covil as a supplier or contractor at the plant.

Despite the judge’s instruction and after hearing all of the testimony, the jury reached a defense verdict. Three months later, Judge Toal threw out the verdict by invoking South Carolina’s “thirteenth juror” doctrine. As explained by the South Carolina Supreme Court, the effect of the thirteenth juror doctrine “is the same as if the jury failed to reach to a verdict…. When a jury fails to reach a verdict, a new trial is ordered. Neither judge nor the jury is required to give reasons for this outcome.” According to Judge Toal, “as the ‘thirteenth juror,’ the trial judge can hang the jury by refusing to agree to the jury’s otherwise unanimous verdict.” She used this incredible power in Crawford to order a new trial, giving the plaintiff a second chance to win a case that was lost.

On at least two occasions, Judge Toal increased jury awards when she believed the juries did not award enough money to the plaintiffs.

In Edwards v. Scapa Waycross, Inc., Judge Toal increased a jury’s $600,000 survival damages award to $1 million. The judge also refused to reallocate plaintiff’s internal apportionment of settlement proceeds to be more reasonable under the facts. The South Carolina Court of Appeals affirmed on both issues.

In Jolly v. General Electric Co., Judge Toal increased an award to a worker and his wife by some $1.6 million. The jury awarded the worker $200,000 in actual damages and $100,000 to his wife for loss of consortium. Judge Toal increased the worker’s award to $1.58 million and his wife’s award to $290,000. She also refused to allow a setoff for the portion of prior settlements that plaintiff’s counsel had allocated to future losses. The South Carolina Court of Appeals affirmed on both issues, signaling “the Court of Appeals will give much deference to the circuit court and is disinclined to disturb these rulings in the absence of an obvious abuse of discretion.”

The combined effect of the trial court’s additur and setoff rulings in Jolly is that, unless reversed by the South Carolina Supreme Court, the plaintiffs will recover more than $3 million ($2.27 million in settlements and $823,333.33 from Fisher and Crosby after partial setoffs), plus interest significantly above the prime rate, for claims the jury determined were worth only $300,000.

ATRA filed amicus briefs in both the Edwards and Jolly appeals. In its Jolly amicus brief, ATRA noted that “[t]he trial court and Court of Appeals rulings essentially give the trial court absolute discretion to replace a jury’s determination of damages with the trial court’s subjective view of what the jury should have awarded.” ATRA further explained:

Additur is virtually nonexistent in asbestos cases outside of South Carolina. For instance, a Lexis+ search of the term “additur” in the Mealey’s Asbestos Litigation Reporter database— which reports regularly on rulings in asbestos cases nationwide—returns only two examples of a court outside of South Carolina awarding additur in an asbestos case in over thirty years. South Carolina, in comparison, boasts two recent examples: [Jolly] and Edwards….

Further, additur is rare in non-asbestos cases in South Carolina and nationally…. In states allowing the practice, empirical evidence suggests “almost no use of additur.”

Nuclear Verdicts

In March 2023, a woman won a $29.1 million verdict against ex-talc supplier Whittaker Clark & Daniels alleging that she developed mesothelioma from exposure to asbestos in cosmetic talc products. The company was forced to file bankruptcy after the verdict and Judge Toal appointed a receiver to “take over its operations.”

In March 2023, a woman won a $29.1 million verdict against ex-talc supplier Whittaker Clark & Daniels alleging that she developed mesothelioma from exposure to asbestos in cosmetic talc products. The company was forced to file bankruptcy after the verdict and Judge Toal appointed a receiver to “take over its operations.”

In 2021, a jury awarded $32 million to a worker whose wife died from mesothelioma allegedly caused by second-hand asbestos exposure. Judge Toal presided over the case. In the 1980s, Robert Weist worked for Metal Masters at a turkey processing facility owned by Kraft Heinz. Weist alleged that he and his father were exposed to asbestos through their work at the facility and brought asbestos home on their clothing. Weist’s wife allegedly died from exposure to asbestos while doing their laundry. Kraft Heinz and Metal Masters were ordered to pay $11 million in survival damages, $10 million in wrongful death damages, and $1 million in loss of consortium damages. The jury imposed another $10 million in punitive damages against Kraft Heinz. What the jury did not learn is that Weist’s wife was not just exposed to asbestos on her husband’s clothing, but that her father, an insulator, and uncle also worked in places where asbestos was present.

The South Carolina Court of Appeals affirmed a $5.125 million award in 2023 in Glenn v. 3M Co.

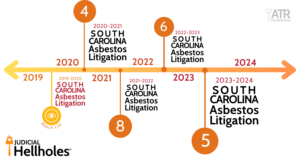

South Carolina’s asbestos environment continues to erode following its initial appearance on the Judicial Hellholes® list in 2020. In the past three years, the state has cemented an unwelcome reputation for bias against corporate defendants, unwarranted sanctions, low evidentiary requirements, liability expanding rulings, unfair trials, severe verdicts, a willingness to overturn or modify jury verdicts to benefit plaintiffs, and frequent appointment of a receiver to maximize recoveries from insurers. The state is a hotspot for asbestos claims.

South Carolina’s asbestos environment continues to erode following its initial appearance on the Judicial Hellholes® list in 2020. In the past three years, the state has cemented an unwelcome reputation for bias against corporate defendants, unwarranted sanctions, low evidentiary requirements, liability expanding rulings, unfair trials, severe verdicts, a willingness to overturn or modify jury verdicts to benefit plaintiffs, and frequent appointment of a receiver to maximize recoveries from insurers. The state is a hotspot for asbestos claims.

In 2017, retired South Carolina Supreme Court Chief Justice

In 2017, retired South Carolina Supreme Court Chief Justice  In March 2023, a woman won a

In March 2023, a woman won a  In 2021, the South Carolina Supreme Court in

In 2021, the South Carolina Supreme Court in