2017 – 2018 Closer Looks

THREE SUPREME COURT DECISIONS SHOULD SLOW LITIGATION TOURISM

Assuming lower courts abide by them, three U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2017 limit the ability of plaintiffs’ lawyers to forum-shop their cases in jurisdictions the American Tort Reform Association calls Judicial Hellholes. The high court’s decisions provide welcome relief for business defendants that had grown weary of being hauled into plaintiff- friendly jurisdictions across the country to which neither they nor the plaintiffs suing them had any connection.

GOODBYE TO THE NATION’S PATENT COURT

In a rare move two years ago, this report named the federal Eastern District of Texas (ED Texas) among the nation’s worst Judicial Hellholes. The court there had become America’s hotspot for patent litigation, drawing plaintiffs from all across the country because of its “rocket docket” of expedited trials, general unwillingness to dismiss cases, a high plaintiff-win rate and larger-than-average awards for damages.

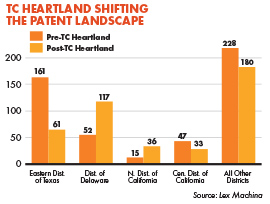

In May 2017, however, the Supreme Court unanimously ended the ED Texas’s reign as the nation’s busiest patent infringement court. The high court’s ruling in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC generally requires patent-holding plaintiffs to bring lawsuits only where an allegedly infringing defendant is incorporated, or where there has been an act of infringement and the defendant has a regular and established place of business.

In May 2017, however, the Supreme Court unanimously ended the ED Texas’s reign as the nation’s busiest patent infringement court. The high court’s ruling in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC generally requires patent-holding plaintiffs to bring lawsuits only where an allegedly infringing defendant is incorporated, or where there has been an act of infringement and the defendant has a regular and established place of business.

Already the ruling is having an impact. Patent cases formerly concentrated in the ED Texas are shifting to Delaware, where many businesses are incorporated, and other states that have real connections to claims. In 2016, for example, 1,647 patent infringement cases were filed in the Eastern District of Texas while Delaware’s federal court hosted just 455. In the weeks immediately following TC Heartland, these two courts experienced a “complete flip” in the volume of cases. Attorneys expect cases to be treated more evenhandedly in Delaware, where federal judges are described as “no-nonsense.”

NO MORE FORUM SHOPPING IN FELA CASES

Last year the Montana Supreme Court earned a place on this report’s Watch List due in part to its May 2016 decision granting state trial courts jurisdiction over cases led by out-of-state railroad workers, regardless of where their alleged injuries occurred. The Montana high court majority reasoned that if a railroad company merely has tracks running through the state it is subject to jurisdiction there.

But in BNSF Railway Company v. Tyrell an 8-1 U.S. Supreme Court majority in May 2017 firmly reversed the Montana high court, requiring state courts henceforth to apply the same constitutional safeguards that apply in all other cases when they hear cases arising under the Federal Employers Liability Act (FELA).

Two years earlier, in Daimler AG v. Bauman, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause does not permit a state to drag an out-of-state corporation into its courts when the corporation is not “at home” in the state and the plaintiff’s injury or the events that resulted in the alleged harm occurred elsewhere. e court de ned a business “at home” in a state as one with sufficiently “continuous and substantial contacts” that make it akin to a local business. Montana’s justices, however, engaged in a strained reading of Daimler and bizarrely limited its application to disputes arising abroad while exempting railroad workers’ cases.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote that “FELA does not authorize state courts to exercise personal jurisdiction over a railroad solely on the ground that the railroad does some business in their States.” She then applied Daimler to the BNSF case. Since the FELA claims were unrelated to the railroad’s operation in Montana, and the railroad did not do such exceptional business in Montana that is could be considered “at home” there, the Supreme Court held that state courts had no jurisdiction over the claims.

THE END OF MASS TORT HOTSPOTS?

Over the years many state courts have earned reputations as Judicial Hellholes, with plaintiff-friendly rules, procedures and judges making them popular destinations for litigation tourism. Such courts draw products liability lawsuits from all across the country, targeting the makers of pharmaceuticals, medical devices, consumer products or asbestos. Examples include mass-tort Meccas in California, the City of St. Louis Circuit Court, Philadelphia’s Court of Common Pleas, and Madison County, Illinois. But in a case that may have the most significant implications for such jurisdictions, the U.S. Supreme Court also ruled that state courts may not exercise jurisdiction over nonresidents’ claims when mixed with residents’ claims that rely on a manufacturer’s general connections to that state.

In August 2016 California’s Supreme Court had allowed 592 individuals from 33 states to join 86 California residents in a lawsuit against a pharmaceutical company. at company, Bristol-Myers Squibb, is incorporated in Delaware, headquartered in New York, and maintains substantial operations in both New York and New Jersey. The nonresident plaintiffs did not purchase, were not prescribed, did not ingest and were not injured by the drug in California. Yet the state high court found that because other plaintiffs were prescribed, obtained and ingested Plavix in California and allegedly sustained the same injuries as did the nonresidents, California courts could exercise jurisdiction over the nonresidents’ claims.

California’s high court also considered Bristol-Myers’ sales revenue in California, research facilities located in the state, its California salespeople and its small legislative affairs office in Sacramento. The court labeled this the “sliding scale” approach, whereby even minimal “contacts” between the business and the state can be added to tip the scale in favor of justifying personal jurisdiction. e ruling effectively subjected any business with significant sales in California to jurisdiction in state courts there, and it was a big reason the once Golden State again ranked prominently in last year’s Judicial Hellholes report.

Thankfully, the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2017 decision in Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Superior Court of California soundly rejected the sliding-scale approach. Another 8-1 majority reiterated that unless the alleged injury arose in a state, an out-of-state corporation is only subject to a lawsuit if it is incorporated or can be considered “at home” in the state by maintaining a principal place of business there. Applying this standard, the high court reversed the California decision as “difficult to square with our precedents.” To establish what is known as “specific jurisdiction,” there must be “a connection between the forum and the specific claims at issue.” Bristol-Myers’ decision to contract with a California company to distribute the drug nationwide, the court found, was insufficient to establish jurisdiction.

The Bristol-Myers decision has altered the landscape for mass tort litigation. The impact is already being felt in St. Louis, last year’s top-ranked Judicial Hellhole and home to more than 1,100 scientifically groundless claims by out-of-state plaintiffs alleging that talcum powder use causes ovarian cancer. Hours after the high court’s announcement of the Bristol-Myers decision, a St. Louis trial judge declared a mistrial in a talc case that combined the claims of a Missouri resident with the claims of two out-of-state plaintiffs with no connection to Missouri.

Two months later a federal judge for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri dismissed the claims of almost 80 out-of-state plaintiffs involved in another talc action, which included just four plaintiffs who either lived or claimed to have used the product in Missouri. Citing Bristol-Myers the judge stated, “There are simply no facts connecting nonresident Plaintiffs to the State of Missouri.”

And two months after that, in October 2017, a Missouri appellate court reversed and vacated a $72 million verdict that had been the first of four such controversial, multimillion-dollar talc verdicts rendered in St. Louis. But, after plaintiffs’ lawyers dug up a connection between Johnson & Johnson and a Missouri company that made talc products, the same trial court judge who declared an immediate mistrial earlier in the year sustained St. Louis’s largest talc verdict, $110 million, as this report went to press. Appeals will certainly follow.

Defendants in other state courts known as mass-tort hubs also are relying on the Bristol-Myers decision to seek dismissals of various claims. As noted on p. 31 of this report, for example, a Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas judge is considering whether to dismiss two-thirds of the court’s pelvic mesh docket. And the Chicago Tribune reports that the decision may also jeopardize Madison County, Illinois’ status as the nation’s epicenter for asbestos litigation.

Contrary to Justice Sonya Sotomayor’s seemingly misinformed Bristol-Myers dissent, injured plaintiffs will not be forced “to bear the burden of bringing suit in what will often be far flung jurisdictions,” because, as always, they can still file lawsuits in their local courthouses, regardless of where defendants may be incorporated or maintain principal places of business, and regardless of where their injuries may have occurred.

The decision will, however, reduce personal injury lawyers’ ability to gather hundreds or thousands of claims from around the country and file them in plaintiff-friendly courts. Instead, plaintiffs’ lawyers will have the choice of ling nationwide mass actions in the defendant’s home state, where their clients live, or where the injuries allegedly occurred. As cases proceed individually or in smaller groups, businesses targeted in mass tort litigation will have, as the Due Process Clause demands, a fair chance to defend themselves and feel less pressure to settle meritless claims.

WILL THE DECISION IMPACT CLASS ACTIONS?

There is an open question as to whether the Bristol-Myers decision will apply beyond mass actions to class actions. Mass actions are individual lawsuits targeting a particular product that are grouped together. Class actions involve one or more class representatives who sue on behalf of similarly situated people with claims involving common questions of law and facts. It remains to be seen how Bristol-Myers impacts lawsuits where a class representative alleges an injury that occurred in the forum state, but many members of the class have no connection to that state. Developments in this area are to be closely watched.

OPIOID LITIGATION

President Trump has now declared the nation’s opioid crisis a “public health emergency.” This important step follows the recommendation by a White House commission, led by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, to “act boldly,” to stem the crisis.

As this epidemic of drug abuse becomes a growing problem for many states across the country, details of a White House strategy remain unclear. But as a recent Wall Street Journal editorial noted, the “horrors of opioid addiction come from many dysfunctions, including too many prescriptions, a decline in work, heroin and fentanyl, easy access from Medicaid, and others.”

Understandably then, as reported by a joint task force of the National Association of Counties and the National League of Cities, many communities are already cooperatively bringing together health care professionals, drug makers and distributors, regulators, law enforcement officials and social service providers “to break the cycles of addiction, overdose, and death” as they work through “partnerships across … local, state and federal levels.”

But having let themselves be convinced that communities can somehow sue their way out of complex opioid abuse problems, some state and local prosecutors have taken a more adversarial approach. Not coincidentally, those doing the convincing are many of the same private-sector personal injury lawyers who got rich beyond their wildest dreams with contingency fees two decades ago when they convinced state attorneys general to let them run lawsuits against cigarette makers.

So no one should be surprised that the personal injury lawyers’ national trade group here in Washington hosted in September a “Rapid Response: Opioid Litigation Seminar” to teach attendees how they too might cash in on such litigation. One of the breakout sessions was even titled, “Opioids: The Next Tobacco?”

Never mind that prescription opioid pain-relievers are not like cigarettes. They were developed to address a legitimate medical need. They require Food and Drug Administration approval and stark warning labels about the potential for addiction, and their lawful distribution is closely regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration. Of course, as we’ve all learned in recent years, what may begin with doctors’ thoughtful prescriptions of lawful medicines for patients’ terrible pain can in some cases end in the streets with overdoses on illegal and deadly drugs such as heroin and fentanyl.

Not to be deterred by facts or nuance, much less the public interest, self-interested personal injury lawyers have talked a coalition of 41 state attorneys general into issuing subpoenas for five drug manufacturers that seek information about how prescription opioids were marketed and sold. Several state AGs have already gone further, ling multi-count lawsuits against drug makers and distributors, with dozens of county and city prosecutors following suit. And most of these prosecutors have hired private-sector lawyers to consult or run their lawsuits.

The prosecutors assert that hiring outside counsel on a contingency-fee basis saves taxpayers money since counsel only gets paid if litigation is successful. is simple rationale, however, overlooks the conflicts of interest and corruption to which such arrangements have often led. A litany of these types of abuses has been chronicled for more than a decade by the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board and a Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times series.

This reporting has revealed that politically influential plaintiffs’ lawyers frequently shop their ideas for potentially lucrative lawsuits against corporate defendants to friendly state prosecutors who then hire the lawyers, expecting generous pay-to-play campaign contributions later.

Thus the American Tort Reform Association (ATRA) urges all policymakers to insist that the public interest in health and safety is never compromised by private interests. is principle has animated ATRA’s reports for more than a decade to push commonsense reform statutes — successfully in 18 states so far — that promote accountability and transparency when public authorities choose to hire outside counsel on a contingency-fee basis.

Too many Americans are suffering serious drug abuse problems, and our leaders must work together to find good-faith solutions. They ought to be relying for guidance on caring and knowledgeable experts inside and out- side of government. Because to rely on trial lawyers instead is to invite other problems that neither policymakers nor their constituents need.

TRIAL LAWYERS’ INFLUENCE GROWS AT THE AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE

As first noted in this report two years ago, the Philadelphia-based American Law Institute for nearly a century has exercised more influence on judge-made common law than any other private institution in the nation. But like a black hole that remains invisible except for the observable oscillations or “wobbles” its overwhelming gravity incites in nearby objects, ALI’s great influence over our courts also has remained invisible to most Americans.

But an April 2010 magazine article published by the plaintiff bar’s leading national trade group served as an observable wobble in the legal universe, signaling dramatic changes at the ALI that should now trouble every business, consumer and taxpayer in America. Of course, to fully appreciate these changes some historical context is necessary.

The ALI’s website explains that it was founded in 1923 by a group of judges, lawyers and professors who were generally “dissatisf[ied] with the administration of justice” and the “uncertainty stemm[ing] in part from a lack of agreement on fundamental principles of the common law” among the various states. So it sought “to promote the clarification and simplification of the law and its better adaptation to social needs, to secure the better administration of justice, and to encourage and carry on scholarly and scientific legal work.”

This was certainly a worthy mission, and over ensuing decades the ALI’s most influential work came in the form of periodic publications known as Restatements of the Law. As the name suggests, restatements surveyed and described existing law, and quickly came to be relied on and trusted by judges, lawyers, legal scholars and law students for their thoughtfully objective analysis. As the utility of and respect for its restatements grew, so did the ALI’s reputation for being above the partisan fray.

Fast forward to 2010. That’s when the magazine article eagerly brought to trial lawyers’ attention ALI’s then soon to be finalized “Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm.” For the first time in the venerated ALI’s history, this restatement went beyond merely reviewing the law and actually recommended fundamental change: an unprecedented expansion of landowners’ duty of care to all visitors, including unwanted trespassers.

Tellingly, one of the article’s co-authors also drafted the ALI restatement and thus was expertly able to cite promising cases in Arizona and Iowa, and otherwise provide detailed guidance for plaintiffs’ lawyers looking to forge a lucrative new line of trespassers’ lawsuits against property and business owners. This new coziness with the trial bar also marked a decided turn away from the ALI’s largely objective past and toward a future of openly subjective advocacy.

Such advocacy was palpable at the ALI’s annual spring meeting in 2017. Up for discussion were two draft restatements concerning the law of liability insurance and consumer contracts which, respectively, could reshape fundamental aspects of the law and further clog civil court dockets with litigation at significant expense to businesses, their customers and just about everyone else.

Only an 11th-hour letter to ALI leadership from many corporate general counsel, expressing “strong concern about the recent direction” of the organization, managed to postpone the anticipated final adoption of the liability insurance restatement at the annual meeting. The letter gravely noted the draft text’s potential to undermine the “plain meaning” of contract terms, disproportionately increase penalties for alleged breaches of duty, and subject insurers to broad, extra-contractual damages for alleged “bad faith.”

Perhaps more troubling is the pending restatement on consumer contracts law. Leaving aside the fact that there has never before been a recognized body of consumer contracts law (there is only contracts law), the three law professors (from Harvard, the University of Chicago and New York University, respectively) charged with drafting this restatement are effectively ignoring the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, much U.S. Supreme Court precedent and the 92-year-old Federal Arbitration Act in their zeal to convince state courts that virtually all arbitration clauses in consumer contracts are “unconscionable” and therefore unenforceable, clearing the way for still more trial lawyer-enriching class actions.

Meanwhile, the American Tort Reform Association and its state-based allies are working to moot the unaccountable ALI’s radical flights of legal fancy. Since 2011 they have driven enactment of bipartisan legislation in 23 states that preempts any additional liability for trespassers’ injuries that ALI-influenced judges may have contemplated. These advocates for reasonable limits on civil liability also stand ready to launch comparable campaigns to contain future threats, too, because even though ALI has as much right as other interest groups to advocate for changes in the law, it is no longer due special deference from judges.

The late Justice Antonin Scalia said as much in a 2015 decision, writing that authors of ALI restatements have, “[o]ver time … abandoned the mission of describing the law, and have chosen instead to set forth their aspirations for what the law ought to be.”

Now the aspirations of American business leaders must include stopping the ALI’s liability-expanding agenda and returning the organization to the laudable scholarship and evenhandedness of its past. Business-friendly members of ALI must become more active and recruit more members like themselves. And unless ALI leaders wish to risk the black hole of irrelevance if their organization were to be wholly captured by plaintiffs’ lawyers and reflexively anti-business academics, they would be wise to invite and welcome broader participation in their underreported proceedings.

Latest News

Plaintiffs’ Lawyers in Judicial Hellholes® Set Sights on New Vital Industry

ATRF has long chronicled the plaintiffs’ bars constant efforts to find their next payday. From hot coffee to baby powder,

Judicial Hellholes

New Jersey Judge Perpetuates Usage of Junk Science in Talc Litigation

Following the implementation of the newly amended Rule 702, ATRF has applauded judges across the country for stepping up to

Judicial Hellholes

Delaware On Verge of Becoming Litigation Hotbed, Supreme Court Has Opportunity to Step In to Avoid This in Zantac Litigation

In early June, Delaware Superior Court Judge Vivian L. Medinilla refused to exercise her essential role as gatekeeper and permitted

Judicial Hellholes